Amazing! Warehouse, Part 7

Rough Draft Part 3

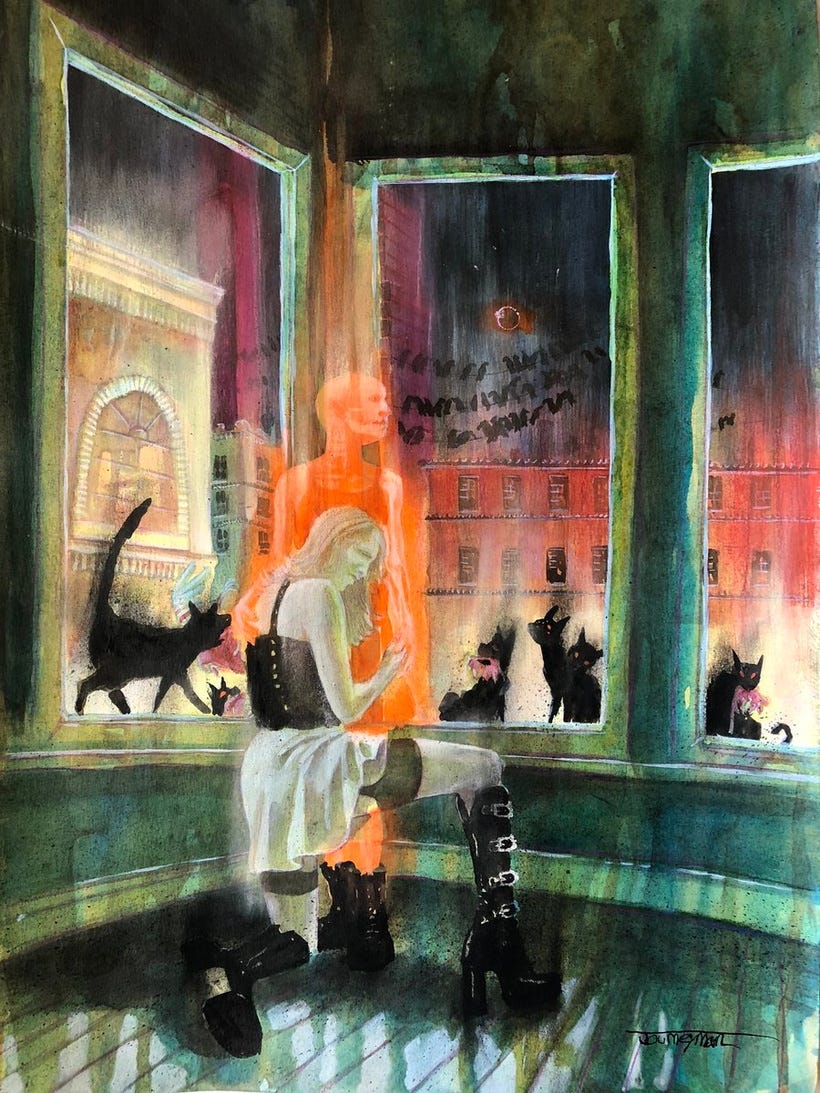

“Life Negative” by Journeyman

Writer’s Note: Below is the continuation of the rough draft, and by that I mean that I feel I am getting close to something publishable, and by close, I mean it’s 10 drafts away from being done. I know that sounds like a joke, but ask any published writer — their work goes through several major drafts and uncountable minor revisions.

I know it’s been a while, and that’s because revision is hard, I’ve been busy, etc…

I’ve been working on this, but completing a section or two, even to the sloppy extent that this is done, has become harder. That’s not bad, it’s just the way it is for me.

I am considering writing on a different topic during those in-between weeks.

The Amazing! Warehouse

Season Creation

A season is a group of related game sessions. In The Amazing Warehouse, that will usually mean 6-20 game sessions.

Seasons have to be created but left unfinished. That is, you have to decide as a group what part of the Amazing! Warehouse, you want to explore, what kind of antagonists you want to face, what kind of characters are appropriate as PCs, and so on, but you can’t decide the path that the game sessions will take ahead of time.

Choosing the Choosers

It’s common for the game moderator (GM) to choose many of the important aspects of a season of play. This is because the GM is typically the one who does the most work and so deserves the most say. I get it, but GMs, I would suggest soliciting ideas from players as much as possible. Some players just want to show up and play, and you shouldn’t push them for contributions, but others are happy to help and contribute. The easiest way to get those contributions from players is to incorporate the choices the players made in character into your version of the Amazing! Warehouse.

The Back and Forth Design of a Season

Start with the Setting

When you design a setting, you should have two poles: The community of Order — the “real” community — that this community most resembles and the effect that Chaos has had on this community — the weird stuff.

The Amazing! Warehouse is based on actual warehouses. That is the real part. Huge stacks of merchandise, long rows, a lot of workers and machines and yet it has many empty places. Chaos enhances some of these qualities. Now it is impossibly large, nearly infinite, and the rows and stacks create a labyrinth, and people do get lost, and of course, some (or all, it’s up to you) of the animals are intelligent, and the humans and animals have been mutated by Chaos.

Include the Conflict

The human workers suffer greatly in this warehouse. To the extent that the PCs are allied with some of the humans, they see the effect of the brutal schedule on the workers. In addition, Oz, the Winged Monkey overseer, is a more direct foe of the PCs. As an animal itself, it does not underestimate the PCs. Oz, like its boss, R. Kam Smith, believes that the animals in the warehouse not only cut into profits by stealing and fouling the warehouse, but those animals also provide aid and comfort to the workers, and workers who are not constantly suffering might be able to organize, and that O and R. Kam Smith will not abide.

The tools that Oz uses are the dragons -- the dogs whose breath is a foul miasma -- to hunt the animal PCs and the spiders -- made from human fingers and eyes -- to spy on the PCs. GMs, you can play those conflicts up or down, but they are there in the setting for you to use.

Other conflicts could include rival animals, workers who don’t like the animals, and the strangeness of Chaos itself, such as portals that open up at inopportune times.

A Role for the Players’ Characters

A great place to look for conflicts is on the character sheet. When you create a character in this game, you make choices that are directly related to the setting, such as what kind of territory your character has access to and what their lair--their home-- is like. GMs should work those choices into the conflicts in the game.

How Setting, Conflict, and Role Influence Character Creation

This is a back-and-forth process. Typically, the GM will give you information about the particular part of the Amazing! Warehouse the game is set in. You will use that information to create your character (rules for character creation follow), and you will pass that character to your GM, who will look at it, be inspired by it, and add to or modify the original setting. Then the GM will update the players, who can then modify their characters again, and you go back and forth until you agree that enough is enough. This process involves negotiation, good faith, and creativity.

How This Comes Together as a Season

You have a setting with lots of flavor, an antagonist, conflict, and a united group of PCs. In my experience, players want their characters to accomplish things, but they also want to explore the setting.

A GM should indulge both desires by rewarding the group for exploration with resources or information that will help them against the antagonist, and reward the group with cool revelations when they act against the antagonist.

The antagonist should have their own plans and modify those plans according to what the PCs do, for good or ill. This is roleplaying that the GM does, and it helps to keep the GM from indulging in “railroading,” that is, deciding what will happen in the game and forcing the players to follow that path.

By intermingling exploration and action against the antagonist as well as making the antagonist a dynamic rather than static threat, the season should progress from beginning through the normal course of play.

It doesn’t matter what the end is as long as the players enjoy the ride. The GM does not need to force anything. Follow what the players do, but make sure to have fun yourself.

What Happens After the Season Is Over

Hey, you build a new season. That’s it. It can be a continuation of the old season, but building a new season gives you a chance to change anything or everything about the setting, conflict, PCs, etc…

Character Creation

Basic Resolution

As a reminder, “The basic rule of resolution is that you compare a trait +/- modifiers to a difficulty number. If you meet or beat that number, you have succeeded. Otherwise, you fail.” The average difficulty number is 2, and difficulty numbers can go as high as 5.

Concept

Your characters are animals—birds, lizards, rodents, possums, cats, dogs, bugs, and so on— that live in the Amazing! Warehouse, a cavernous labyrinth of a building with boxes piled high and workers both human and robotic moving efficiently and relentlessly like cogs in a clock. But in the shadows and nooks and crannies, the animals live, and in the liminal space between the shadows and the light, the animals sometimes meet human allies who provide them with food, comfort, and even, on occasion, medical care.

Your characters have human-level intelligence but they are still animals. They can communicate with each other, but in some key ways they are different from humans. They cannot communicate easily or well with most humans, and, for the most part, concepts such as numbers over three, the exact meaning of human speech, and the operation of human technology are difficult for them if not beyond them outright.

But these animals can make plans, can understand the basics of human interaction, and have their own natural advantages.

The PCs have animal “powers” as well as mutant powers, but they also have animal disadvantages. It’s not easy living in the Amazing! Warehouse.

Character Creation Is Setting Creation

As you create your character, you will detail your traits and powers. These choices will help the GM flesh out the setting. Suppose you add air conditioning to your Lair. The GM might decide that the AC makes your Lair a hangout for other animals. You like that idea and you go with it, thinking of how you can turn that to your advantage. Or suppose that you choose teleportation as your power, but you have to travel through a hellish dimension to teleport. Your GM might decide that on occasion, the denizens of that hellscape follow you out, or perhaps they have already done so.

Traits

Traits are keywords that help to define how your character affects the game world and vice-versa. In character creation, you assign numbers to your traits, the higher the number, the better the trait. In addition, you also assign one specialty to each trait. Both traits and specialties are discussed in greater detail below.

Powers

Powers are magical, chaotic abilities that allow you to break the laws of reality. They never come without a cost. Powers are literally unnatural. They are the intrusion of Chaos into a world of Order, or the capture of a sliver of Chaos by a being of Order (hey, that’s you!). In this game, everyone has a power, and a few maybe more than one.

You can give your character any single power you like, but your power must have a flaw that limits it. These powers are often dangerous or uncomfortable to use.

Unlike traits, powers do not have a number associated with them.

Traits

In the Amazing! Warehouse, your characters have certain Traits that are common to all player-characters (but not necessarily game-moderator characters).

These Traits are Territory, Lair, Instincts, Humanology, Contacts, and Allies. Each of those traits needs to be defined for your character. Defining your traits also helps create the setting. For example, if your Lair is the garbage bin outside the employee break room, the GM will likely make that area important.

Specialties

In addition, you must assign a Specialty to each of your Traits. Most Specialties give your Trait a +1 modifier in certain circumstances, the ability or skill to do something that others can’t, or ownership of a special item or location.

Specialty as Modifier

An example of using a Specialty as a Modifier bonus is a dog whose Instinct specialty is Menacing Growl. Any dog can growl, but your growl gives you a +1 bonus to your Instinct when you try to intimidate or frighten others.

Specialty as Ability or Skill

An example of using a Specialty as an ability or skill is an animal that can count due to its exposure to humans. That animal would have the Specialty of Count under Humanology. The character receives no bonus due to its specialty. The bonus is the ability to count, a powerful ability in a warehouse.

Abilities and skills are never magical in nature. For that, see Powers.

Specialty as Item

An example of using a Specialty as an item is a raccoon who owns a nasty spear / shiv made from a discarded razor blade attached to a fiberglass rod.

Items can be Specialties of almost any Trait, though it’s rare for that Trait to be Instincts. An item can give you a bonus or ability in a particular situation, depending on the item. Using a Specialty on an item means that the item is attached to you in the setting. Even if the item is stolen from you or broken, you know where to get another one or how to make another one. This doesn’t mean that it’s easy to re-equip, just that it’s within your ability to do so. Which Trait should you use? That depends on the source of the item. Did you get it from a human or from your Territory or from an Ally? Is acquiring such items part of your Instincts? Is the item mostly associated with your Lair? In short, it’s up to you and your GM.

Unique, Inherent Abilities

If a species has a unique ability, you only need Instincts to access it. For instance, possums are experts at feigning death. This is an instinctive ability that they do not have to buy as a Specialty. Similarly, certain snakes are poisonous, birds can fly, and so on. None of those abilities need to be bought as Specialties.

Description of Traits

These traits not only define your character, they also help to define the setting. Everything you pick here is a bright signal to the GM to include something that highlights a strength of your character or exposes a weakness. In addition, the details you pick for your character will also help the GM populate the world. Your contacts, your allies, even the choice of instinctive specialties help.

Instincts — This is your ability to act as an animal of your species. Specialties include Track, Sense Hidden Items, Fight, Run, Climb, Leap, Slither, Fly, Hiss, Bark, Roar, Purr, Sneak, and so on.

Humanology -- This is your ability to understand humans and their technology as well as to be understood by them. Specialties include Speech, Count, Writing, Electronic Items, Body Language, Cute,

Territory -- This is your corner of the warehouse, the area that you control, whether by yourself or as part of a family or gang. Barter is the rule in the Amazing! Warehouse, so defining your Territory is important because defining your Territory defines what you have to trade. Items are common Specialties associated with Territory, but a characteristic of the Territory could be a Specialty too, such as Well-Defended, Central Hub, or Obscure Corner. Your relationship to the Territory could be a Specialty as well: Respected, Knows the Secret Places.

Lair — Also referred to as a nest or home. This is your most prized possession. The higher your score, the more comfortable and secure your home is. This is where you rest, where you have a cache of food, where your family lives, and it should be the safest place you’ve been able to make for yourself. Anyone trespassing is starting a deadly fight or simply looking to eat you or maybe be eaten. An animal with a poor lair is in dire straits, and an animal with no lair is either in great danger or greatly dangerous or both. Most Lair Specialties are about characteristics of the Lair: Well-Defended, Hidden, Electrical Access, Luxurious, Climate Controlled, and Guarded.

Allies — This measures the animals or people you can count on for help in a season of play. Your score in this Trait measures the effectiveness of these allies -- friends, family, or even just someone who owes you a debt. You can call upon two allies, once each per season, and they will help you for a scene or two, and by help, I mean they’ll put their lives and reputations on the line for you. You’ll owe them after that, and if an ally gets killed or seriously hurt or screwed over helping you, your Allies score goes down by 1. Specialties for Allies can describe their relationship to you: Family, Loyal, or Shared Experience or the expertise of an Ally: Diplomacy, Seduction, Killing, Protection, or Tracking.

Contacts — These are the people or animals who are in the know who will tell you stuff, whether it’s gossip, industrial secrets, secret lore, and so on. Your score in this Trait measures the effectiveness of your gossip network and how willing they are to help you.

Some people in your life are “Contacts” if you ask for some information and “Allies” if you ask them to put themselves at risk for you. You can use Contacts once per game session per point in this trait.

When you use a Contact, your request is rated on a scale of 1 to 4. If you make a request that is higher than your Contacts score, you’ll have to do the contact a favor, give them a useful or interesting item, do some investigative work of your own, or otherwise put yourself out. Similarly, if you want to use your Contacts more often than your Contacts score would allow, you have to do the contact a favor, give them money, do some investigative work of your own, or otherwise put yourself out. Contacts have Specialties similar to Allies, though their area of expertise tends to be more information based: Comings and Goings of Workers, When the Good Stuff Enters the Warehouse, Secret Passages, and so on.

Powers

Here’s how you create powers. First, think of something cool you think would be fun in a game. Consider the standard array of super-powers: laser eyes, flight, turning invisible, telekinesis, super-strength, telepathy, and so on. Second, make it weird. Third, think of a drawback that makes it difficult or unpleasant to use the power, possibly related to the weirdness. This is the narrative way of making chaotic super powers.

Here are some examples:

Mimicry -- When you activate this power, humans treat you as if you were not just human, but a comrade or co-worker as well. Your Humanology increases to 5, but your Instincts decrease to 1. Nothing about your actual appearance changes, and humans only imagine that you are giving proper responses to social cues and such. When you stop mimicking a human, your Humanology score returns to its normal value, but your Instinct score remains at 1 until you have spent the same amount of time as an animal that you did as a human. You fear that if you mimicked a human too long, you’d never regain your Instincts.

Astral Sense -- You can perceive the Astral Plane. This lets you perceive auras rather than the physical world, and you can use Instincts to interpret these auras. While using Astral Sense, you cannot sense anything in the real world, including time. This is a dangerous activity to attempt alone since you may spend hours or even days lost in Astral space. Wise practitioners have friends or allies who wake them after a specified amount of time. Astral Sense is not limited to sight. Some animals hear the songs of the Astral forest or sniff out the scent of the Astral ocean or something similar.

Walk through Walls -- You fold yourself and enter another dimension, seeming to slip through a tear in space-time. While in this other dimension, you can perceive the real world as through a dark glass. This is where the chase begins. You cannot stay in this dimension. You are an interloper, and something in it wants to hunt you. You run and run, and make your exit, having traveled seemingly instantaneously and avoided any obstacles in between your entry and exit. One day, the hunter in that other dimension might follow you out.

Building a Character

Building a character merges your personal creativity with the game’s rules. As you create a character, you are also creating details that your GM can and should use in the game in addition to the characters and settings that the GM comes up with. What is on your character sheet should be in the game as well. GMs, it’s as if the players have done some of your work for you.

So start by choosing an animal, which can include insects or other bugs. It does not matter how little your animal is, as long as it can be seen. It does not matter how large it is, as long as it can hide.

Build Points

You have 60 Build Points (BP) with which to create your character. You can spend these as follows:

Common Traits -- Territory, Lair, Instincts, Humanology, Contacts, and Allies -- cost 4 BP per point in that trait. You can also purchase Territory and Lair more than once, to indicate multiple territories and lairs. More on that below.

Specialties cost 1 BP per Specialty. Remember that each Common Trait you have comes with one Specialty for free.

Powers cost 4 BP per power. Although Powers are Traits, they are not rated. Instead, they simply allow you to break the laws of reality.

If you put 0 or 1 points into a Common Trait, you’ve created a weakness for yourself. 0 in Contacts, for example, means that you are shunned or no one wants to help you except for an Ally or two (and 0 in Contacts and 0 in Allies means you are completely shunned). This isn’t bad, necessarily. It can be interesting. Why do you have that weakness?

Similarly, if you put 3 or 4 points into a Common Trait, you’ve created a strength. Why is your Instincts 4 with a specialty in Fight? Have you lived a brutal life in which you test yourself against everyone, and you often win, and when you don’t, you don’t mind taking a beating? How did you come to be this way?

You may buy certain Common Traits -- Lair and Territory -- more than once if you wish. You could buy Lair 4, for instance, to show that you have a secure, spacious home, but you could also buy Lair 1 as well, a little bolt hole that you can run to if your better-known Lair is ever assaulted. Similarly, if you have Territory 2 (Cardboard Box Storage Area), you could also buy Territory 2 (Snack Room Garbage Bin), and now you have two items to trade. Each additional Common Trait also comes with a Specialty.